More than ever, manufacturers feel the pressure to keep up with their competitors and manage regulatory and certification requirements the best they can.

This has driven at least a couple to design and build laboratories in the last few years. They don’t like to discuss specific dollar amounts, but investments are considerable: There’s the physical space and equipment, materials and, in some cases, the dedicated staffs to work the labs. General estimates go into the millions or tens of millions.

Other producers have developed and accumulated labs over the years, as they’ve grown organically or acquired other firms.

These laboratories make up just one component of the testing equation. Many test initial concepts via computer simulation before building prototypes. After products undergo their rigors in the lab, later-stage testing often is performed in real pools and spas across the country.

“Expanding your labs and improving capability is just what you do as a responsible manufacturer,” says Kevin Potucek vice president of product management for Hayward Pool Products in Elizabeth, N.J. “You’re continuing to strive to improve reliability and performance.”

Here, take a look at some of the labs, the driving forces behind these investments, and the progress made in testing the last few years.

Taking charge

Whether these manufacturers have new labs that test a relatively narrow product line, or if they have multiple, seasoned facilities, they place the emphasis on the same principle: Taking initiative.

AquaStar Pool Products

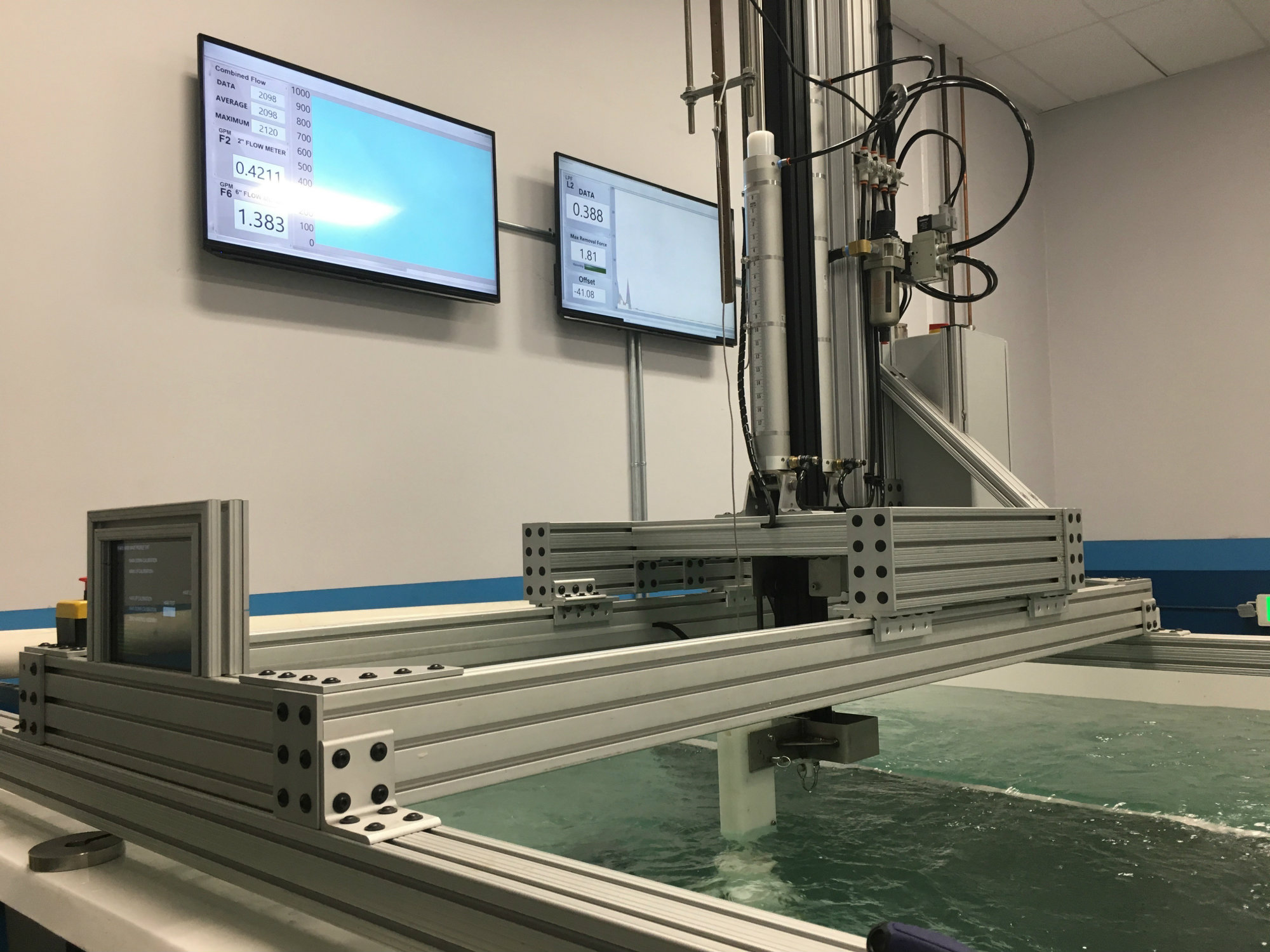

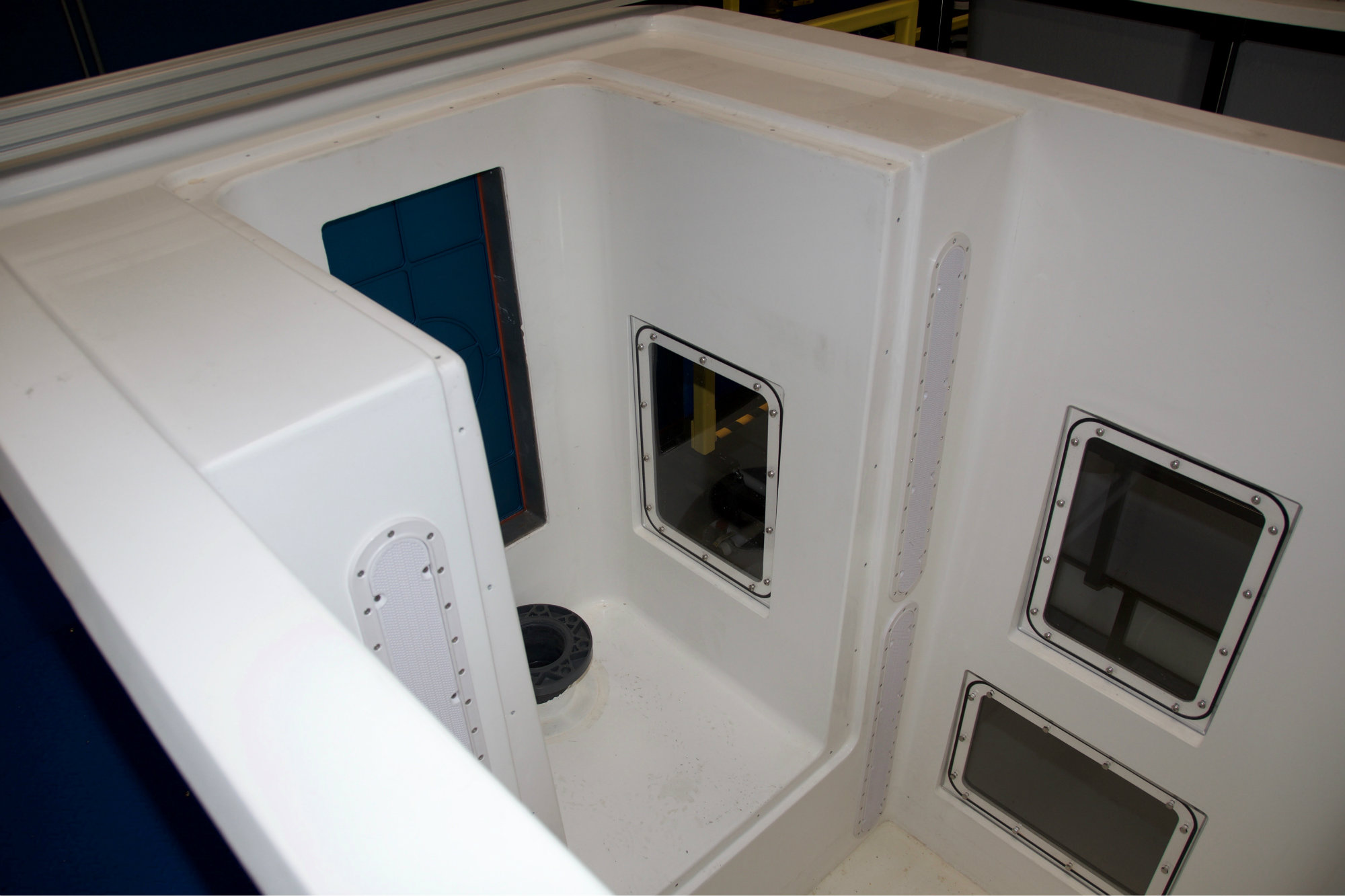

Producers seek to be proactive with their facilities. For instance, AquaStar Pool Products, the San Diego-based producer of drain covers and other hydraulics-related components, just completed a three-year build-out of a new lab that has been approved by Underwriters Laboratories to conduct certification testing on its products.

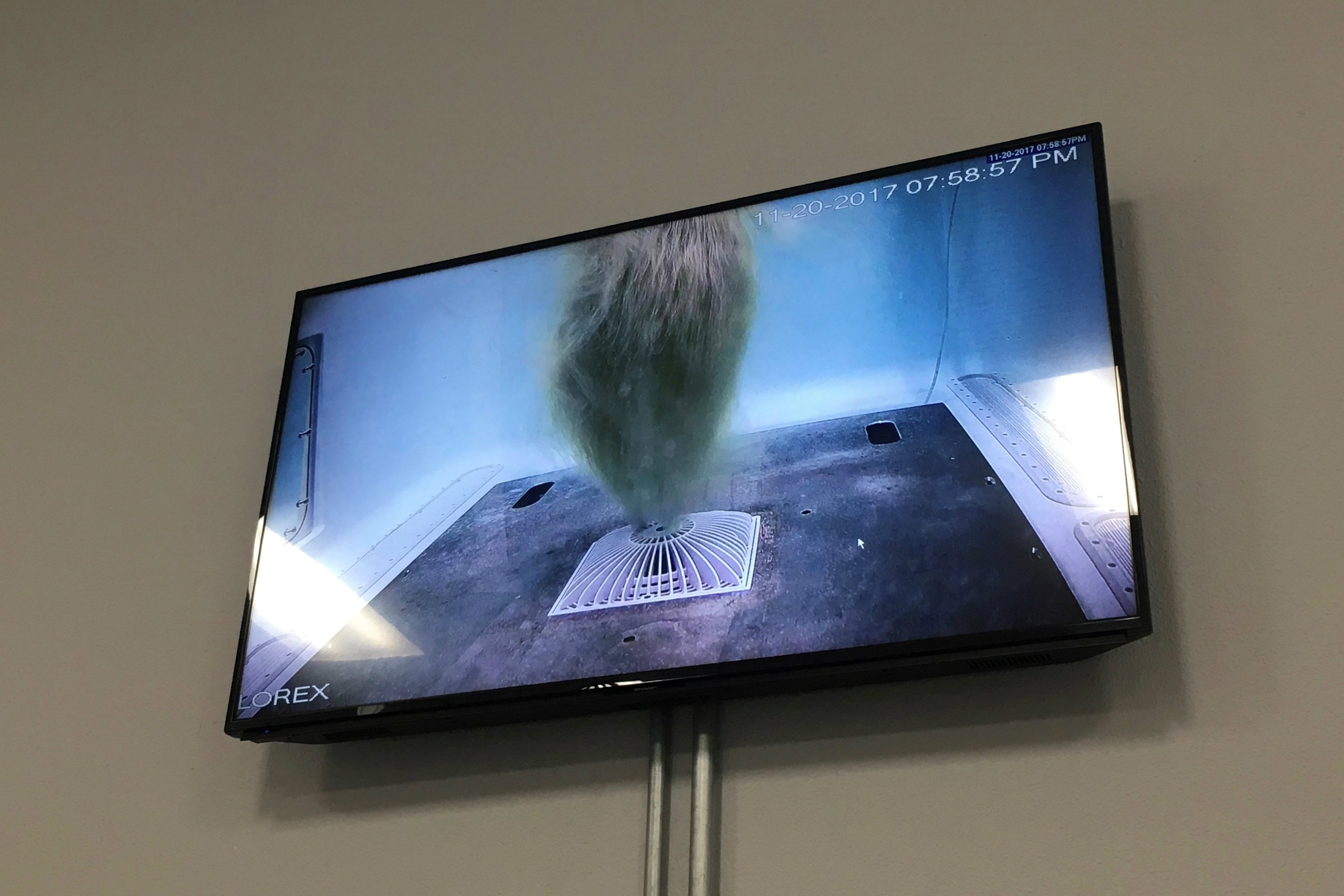

The lab is largely designed to focus on the more difficult tests contained in APSP-16, the drain cover standard. Robots wave devised heads of human hair for the test that determines whether tangling in the drain can occur at certain flows. The machines also perform the body-block test, in which an 18-by-23-inch element simulating a torso is set against a drain to see if a complete block can occur, resulting in a vacuum.

Through a special program called witness testing, AquaStar can conduct its own testing to ensure its products meet APSP-16 and other standards. But, to gain this ability, producers must go through an extensive process to prove that their equipment and methods comply with the requirements included in the applicable standards. AquaStar outfitted its laboratory with cameras and provides UL with real-time access to the data, so a staffer with the third-party testing organization can essentially monitor the testing remotely. And, according to the agreement involved in witness testing, UL officials have the discretion to make in-person appearances to watch scheduled testing, rather than monitoring it remotely like normal. They can do this without warning.

To gain this approval, manufacturers must document such things as the calibration of their equipment and establish that their procedures and training will yield consistent testing and reliable results.

It took AquaStar about a year to design the lab, then another two to build it out, says Steve Barnes, director of science and compliance with the manufacturer.

The company was largely motivated by the desire to make sure testing is performed correctly — and to test for the right characteristics. “I thought, ‘We need to control our own destiny,’” Barnes says.

In its design, AquaStar sought a cutting-edge facility not only to conduct its own proprietary and certification testing, but also to provide a venue for the round-robin testing that takes place as part of the standards development, as Barnes heads up the Association of Pool & Spa Professionals Technical Committee, which works on writing the various industry standards.

And while the lab is mostly equipped to test the company’s drain covers to APSP-16, Barnes and company owner Olaf Mjelde wanted to conduct the testing and use the data to help fine-tune.

“When you send something to a certification lab, they are looking to make sure it meets the standard,” Barnes says. “They’re not trying to say, ‘You know, if you just change this design — if you move this, if you make this bigger or smaller — you’re going to have better performance.’ That’s not their role.”

Other manufacturers also are set up to host certification testing. Hayward Pool Products and Zodiac Pool Systems, for instance, have received approval to conduct certification testing in their own facility with an engineer from the applicable third-party lab. They, too, must show that the equipment is up to snuff and well-maintained, the staff qualified, the test methods mirror those used by outside labs, and that the facility generally yields consistent results.

These manufacturers believe that in-house testing helps bring products to market faster: It’s easier to get an engineer to login remotely or even visit the facility than it is to arrange for testing in a third-party lab, they believe. Not only that, but they want to benefit directly from the knowledge that can be gained through the protocols.

“It’s hard to find people from outside [the industry] who really understand pool products,” says Mark Bauckman, vice president of engineering for Zodiac, based in the San Diego suburb of Vista, Calif. “They’re very specific to our application. So the more you can build that [knowledge] in-house, the more valuable it its.”

In some cases, even these manufacturers must take a product to a third-party lab if, for instance, they don’t have the exact equipment or test method in place. In other cases, it may be more efficient to use somebody else. Even in those cases, these manufacturers want to be prepared for the results by performing some testing ahead of time.

“Our lab allows us to test all those configurations and know the answer before we have the expensive test, ” Barnes says.

Making the rules

Some producers want to test their products for performance factors beyond those in the governing standards.

This was the case for Glen Cove, N.Y.-based filter-products maker Pleatco. Eight years ago, with new owners, the company decided that not only did it need to generate its own data rather than relying on that of vendors and other sources. It also wanted to embark on performance testing that went beyond the protocol found in NSF-50, the only standard that really applies to this product category. While they thought the standard establishes parameters for turbidity prevention and performance early in a product’s life, Pleatco officials wanted to know how much time would pass between needed cleanings, and how the product would do later in life.

One of three testing spaces for Pleatco. Two are for research and development, while the other is dedicated to NSF-50 compliance.

“We want clean water, we want pure water, but at the same time, the customer is expecting to withstand a long period of time before he or she has to take the cartridge out and clean it off,” says Richard Medina, senior vice president of engineering for the firm. “We had to come up with another way to do this to accurately replicate what the field experience is.”

Abhi Pillai, Pleatco's director of research and development, in another of the manufacturer's testing labs.

Plus, they wanted to measure their products against the competition.

So the company developed a three-part testing operation. The first laboratory features two duplicate rigs for comparative testing. It also includes a spa, so products can be checked in that environment. A second area is dedicated to NSF-50 testing. Then an outdoor lab includes two identical pools with the same equipment, plumbing and dimensions, for more comparison testing. Overhead video cameras record time-lapse films.

To perform much of the testing, they developed what they call the Pleatco cocktail, a mixture of oils, clay-like substances and other components that pool filtration is meant to capture. They apply the unpleasant mix, which has the consistency of a shake, to see the effects not only on Pleatco’s filtration products but also on competitors’.

Industry advancements

In addition to certification requirements, simple market pressures have driven progress in product testing.

“The bar continues to be raised on what products are capable of doing,” Potucek says. “So a lot of the lab’s task is design validation testing. DVT capabilities have increased dramatically over the years for Hayward and, I suspect, others, in terms of both technology and protocol.”

On the technology side, the Internet of Things has made arguably the biggest difference, producers say. By connecting test units to the internet, engineers and staff can gather immediate data from remote locations. Not only does this simplify the staff’s job, but it speeds up data acquisition, possibly helping to fine-tune and bring products to market faster.

“Testing is all about gathering data and getting that data back to the design engineers to make decisions,” Bauckman says. “So the more data we can get and the faster we can get it, the quicker we can make decisions to either proceed or make changes [to a product].”

In addition to this connectivity, AquaStar and Barnes placed a heavy emphasis on finding the most accurate measuring equipment possible. They moved to more expensive magnetic flow meters and differential pressure gauges.

“If you can get to this level of accuracy, then you can find the true limits of design,” Barnes says.

Progress comes even from the simple act of growing space to accommodate more test tanks and ensure that a proper sample of units is tested.

“The quantity of units that we test now is enough to be statistically relevant,” Bauckman says. “We need a [sufficient] sample size of the products you’re testing so that if you get a few failures, you’ve got the proper statistical size to be able to go back and calculate whether you need to do something about that. You can’t do that by testing a few in a tank.”

Some of the progress manufacturers have made results from the increasing diversity of pool and spa products. In many cases, this requires firms to undertake much more testing.

For instance, automation products require a process that Zodiac calls integration testing. Manufacturers need to learn how their controllers will work with all the possible components with which they will connect. That means all parts, by all brands. The relationship also goes in reverse: Makers of the various components also want to see how their pumps, heaters, sanitizers, etc. will interface with various controllers.

“We’ve gotten more sophisticated in how we’re able to test all those integrations …,” Bauckman says. “It’s a big matrix of interoperability between things.”

Products also must be tested for the variety of conditions to which they will be exposed, Potucek says. That’s one of the reasons that test cycles vary so much from SKU to SKU. End-stage testing, after the product has been developed, can take anywhere from weeks to months or more.

“The more consistent a product’s use and environment, the easier it is and perhaps the shorter time it takes to test,” Potucek says. “For example, you have to consider even how deep is the application? That can make a big difference on how much water pressure it’s exposed to. And where is it in the plumbing: Is it inside a pressure vessel or is it just in the pool itself so you only have to worry about the depth of the water?”

Pool cleaners can pose a particular challenge here, as they will have to work on a wide range of surfaces and in limitless shapes of vessel.

While there is always room for improvement, these manufacturers believe the pool and spa industry has come a long way in its testing.

“The industry itself has evolved a lot in the last 10 years,” Bauckman says. “For us, over the last five years it’s been a very conscious effort to focus on product quality. That means investing more in testing, ensuring that you’re testing all our products through more quantities and putting them through more rigorous testing.”