What’s strong enough to lift a gunite shell out of the ground? What has enough force to crumple fiberglass?

The answer is hydrostatic pressure. If it can destroy pools constructed of rigid materials, then vinyl liners do not stand much of a chance, right?

Actually, this is where vinyl has a distinct advantage: A floating liner is no big deal when compared to a vessel that has been heaved upward, damaging the deck and cracking the shell.

So while clients may not be thrilled with the sudden appearance of a balloon-like protrusion in their beautiful vinyl liners, worse things can happen.

Besides, there are several surprisingly simple fixes that could go a long way toward keeping hydrostatic pressure at bay.

A groundswell of issues

First, it helps to have an understanding of what causes the problem.

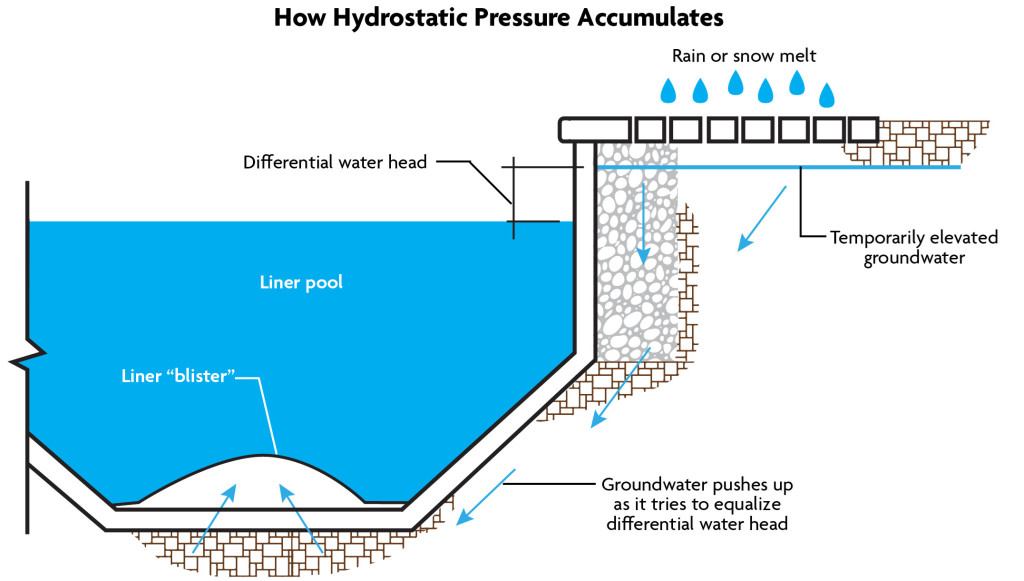

When liners float, some pros tell their clients that they have a groundwater problem. It’s a common misconception. But water underneath the shell isn’t the issue, at least not initially. So long as the water level in the pool is higher than the water in the ground, there will be enough internal pressure to keep the liner in place.

But water has a funny way of getting into places it doesn’t belong.

If the surrounding landscape doesn’t provide proper drainage and shed water away from the pool, then water will collect around the perimeter from rain and snowmelt. This accumulation will eventually connect with groundwater and potentially swell above the pool’s water level, generally 4- to 6 inches below the ground. The water levels in the pool and ground will want to equalize. A downward pressure from the surface causes the groundwater to exert pressure up against the shell.

Water rising slightly above the surface of the pool — even as little as 1/8 inch — could be enough to cause the liner to lift.

So, what can be done about it? Pros should consider the following time-tested techniques.

Well points

Brian Worley is a big believer in well points.

The Chattanooga, Tenn. builder is accustomed to digging pools in rich, water-retaining clay. “A lot of mud we encounter around here is what we call gumbo mud,” says the president of Everclear Pool and Backyards Co.

The ground has proved problematic for those with poor onsite drainage. When spring rains saturate the state, Worley can expect a flurry of calls from people whose pools are bulging at the sides or bottom.

The quick fix here is to run a pump between the liner and pool wall to remove the trapped water, and then partially drain the pool to work out any wrinkles.

But a well point would provide a more permanent solution. The concept is simple. A 12-inch diameter pipe goes vertically into the ground, providing a path of least resistance for the water to well up into.

Here’s how it’s done: Begin by drilling a hole about 1- to 2 feet deeper than the pool’s deep end, just outside the deck. It must be wide enough to accommodate the pipe. Place a 1-to-2-foot layer of ¾-inch gravel in the bottom. Then install the 12-inch PVC pipe and backfill around it. In cases of extreme groundwater, Worley recommends an 18 or 24-inch diameter pipe.

An automatic submersible pump is placed in the bottom and set up so it’s triggered when water in the pipe reaches a certain level. A horizontal discharge pipe near the top of the vertical installation channels the water offsite. Put a lid on it and you’re good to go.

Worley confesses that determining the best well point locations can be a bit of a guessing game. In some cases, for instance, a bed of shale can obscure the original source as water is channeled across it and toward the pool.

But in some situations, pipe placement is obvious, such as between the pool and a nearby creek, pond or other body of water.

Sometimes, it’s just a matter of punching holes in the ground to see which one fills with water. “It’s a bit of a witch hunt, really,” Worley says.

Fortunately, it doesn’t need to be an exact science. If you give the water a place to go, it will likely oblige, even if the well point isn’t ideally located.

“I think people don’t understand sometimes what water will do,” Worley says. “If you provide zero resistance for that water, it’s going to find that well point.”

Some situations call for two well points — one at the deep end and a shorter stick of pipe at the shallow end.

French drains

A French drain is not to be confused with a surface drain, which carries water away at first flush. Rather, a French drain offers subsurface hydrostatic relief.

“It’s a pretty effective method of getting water away from structures, pool shells and decks, especially when you’re dealing with upslope site conditions,” says Scott Cohen, owner of Green Scene Landscaping & Swimming Pools in suburban Los Angeles.

Begin by digging a trench around the pool. This may require cutting a swath of deck to place the drain close enough. The depth depends on site conditions and how much water is present, but so long as the horizontal pipe is well below the pool’s water level, it should be in good shape. (Remember, external water pressure is only a problem when it rises higher than the pool’s water level.)

Then drop landscape fabric into the trench and put down a layer of pervious gravel — an important ingredient since it provides the water a path of least resistance. The fabric will encase the bed of gravel like a burrito. Alternatively, the professional can roll a sleeve of fabric over the pipe like a sock. Either method will prevent debris from clogging the pipe.

Next, it is time to install the pipe, which has a series of holes. During this step, take care to avoid one of the most common mistakes — incorrectly orienting the holes. Place the pipe with the holes facing downward. This way, the water can seep up from the ground, enter the trench, then rise into the pipe through the holes at the bottom.

Channel the water into a solid drain pipe to carry it off the property or tie it into a sump-pump system.

Winterize wisely

Homeowners most often discover billowing liners after removing the pool cover for swim season. This can easily be avoided during winterization.

Pool pros commonly lower the water well below the skimmer throat before closing a pool. They might be able to get away with this on steeper sites that shed water more effectively. But use caution on flat properties.

Though these sites often are required by code to sit 1- to 2 feet higher than street level so water can shed away from the property, this might not be enough to prevent groundwater build-up. Dropping the pool water too low during winterization only increases the chances of hydrostatic pressure.

“As soon as that happens, blistering occurs,” says Neil Anderson, principal of Terracon, an environmental consulting firm based in Kansas City.

His advice? “When you winterize your pool, don’t lower the water any lower than you absolutely have to.”

Sump’thing to consider

The story above addresses several aftermarket approaches to prevent liners from floating. But to keep a liner where it belongs, installers are best served by building it right to begin with.

Matt Rozeski developed what he believes is a pretty smart system for keeping liners intact. The owner of Penguin Pools, serving southeastern Wisconsin and the Minneapolis/St. Paul region, installs a sump below the liner at the deep end.

This is done with pool installations on soggy sites. “If it’s soppy, if I’m stepping and I see water, I automatically put it in the quote and tell them they’ll have to sign a release if they don’t put the system in,” Rozeski says.

To do this, Rozeski overdigs the deep end by 18- to 24 inches and puts down a layer of chipped limestone. He then configures a rectangle of 2-inch PVC pipe. He drills holes all the way through the plumbing every 6 inches, rotates it a quarter turn, then drills another series of holes, offsetting them from the first ones. (See video above.)

“If we’re using that pipe to pull water out, we want that water to come in as soon as possible,” Rozeski says.

He places landscape fabric over the pipe and piles more gravel over it until it reaches the elevation for the shell’s deep end. The sump is connected to the equipment pad via a 1.5-inch flexible pipe.

“Up at the equipment pad, we add that to the manifold, which has its own valve,” Rozeski explains.

This way, when the user turns on the discharge valve, water is drawn out from under the liner.

The trick is teaching clients to be proactive. Instead of waiting for the liner to float, they should discharge the water after each rain.

There is a way to retrofit existing pools with a similar system. The contractor must remove the liner, cut out the main drain and use that line as the sump. It’s not ideal. For one thing, the main drain has been eliminated. For another, many older pools weren’t backfilled with the pervious stone that relieves pressure around the vessel. Liners on these pools will float much more quickly, and wrinkles will likely remain after the water has been removed via the sump system.

“Homeowners say it worked great until that one time they went on vacation,” Rozeski cautions.