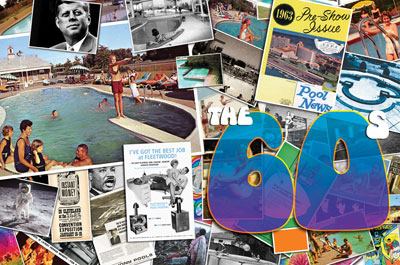

The pool industry in the 1960s was like a toddler first learning about the world. It lurched forward on unsteady legs, grasping at everything in its path with a wild rush of energy and enthusiasm.

In 1968, one executive who had just entered the business told Pool News he was trying his best to understand the distribution channels. “It’s a bit confusing,” he said. “In the pool industry, everybody sells to anybody, any time, at any price.”

This free-for-all occurred because the industry was still forming. Lower production prices meant that for the first time, a middle-class family could own a swimming pool, and thousands of average Americans, having been influenced by Hollywood, were lining up to feel like movie stars in their own backyards.

“The word ‘pleasure,’ like the word ‘profit,’ is firmly entrenched in our national vocabulary,” said Buzz Hays, president of the National Swimming Pool Institute, in 1965. “It’s no longer a dirty word. Whole industries were built on it, ours included.”

The act of creating a brand-new market gave the entire industry a sky’s-the-limit feeling, similar to the dot-com boom of the 1990s. Optimism ruled the day, with each year dramatically outpacing the one before, and new trade associations popping up like superheroes eager to solve any problem facing this prosperous world of boundless innovation.

As the industry rocketed forward, Pool News followed suit, becoming larger and more sophisticated. By 1965, the homespun birth and wedding announcements were gone, replaced by hard news and information on products.

Not that the magazine had lost its personal touch. The pages still contained humorous stories about individual industry members, and many ads featured photos of the very men responsible for the products being sold. No doubt their friendly faces provided a sense of security for buyers who could actually see the man in charge of that filter, and be told, “If you have a problem, call him.”

Another personal touch from the 1960s was the industry’s love of anything silly. It was a decade of costume parties, practical jokes and gag gifts — a typical photo in Pool News might depict a startled-looking pool builder tentatively holding a baby alligator while members of his local association laughed in the background.

All told, the ’60s was a time of enormous growth and self-definition, as the industry learned to see itself as distinct from other markets.

The future is bright

A number of factors contributed to the industry’s dramatic growth.

First was the advent of lenders entering the pool market. By the middle of the decade, many home-owners were including pools in their mortgages, a concept that began in Phoenix and spread like wildfire as more consumers realized they could own pools with barely an increase in their monthly payments.

The ’60s also gave rise to package pools, especially in the Northeast. During its formative years the product had developed an unsavory reputation, due in large part to shady practices involving sales of franchises. However, by the mid- to late ’60s, package pools had found a solid niche, with many well-known aquatic stars lending their names to the product.

The decade brought significant advances in pool equipment as well. Filter technology underwent a transformation with the arrival of high-velocity sand filtration. Rapid sand filters offered the same benefits of sand and gravel, but relied only on sand, an innovation that shrank filter size and upped performance.

Pumps changed, too, shifting from cast iron to bronze. The new material was actually a mixed blessing at first because the high cost of brass raised the price of the pump, and manufacturers reportedly began sacrificing quality to compensate. As late as 1969, a number of builders, particularly in the East, would not use bronze pumps because they claimed their ability to self-prime wasn’t equal to the older cast-iron models.

But mostly it was unquenchable demand for a fun, sexy, glamorous product that fueled the industry’s meteoritic growth.

The giants

Today, the pool and spa business is divided roughly into five segments: builder, service technician, retailer, manufacturer and distributor — with overlap in the first three sectors. But back in the 1960s, those roles were in flux, with many companies dipping into different niches.

Against that backdrop, none were more diversified than the nation’s two largest builders: Anthony Pools and Blue Haven Pools. The Southern California firms engaged in a friendly — and not-so-friendly — rivalry throughout the ’60s, with each vying for a bigger piece of American pie.

Founded in 1946 in Los Angeles, Anthony Pools (later to become Anthony & Sylvan) was content to remain in the Golden State until 1965, when the firm began an aggressive expansion plan. In quick succession, the company opened offices in Nevada, Arizona, Pennsylvania and Texas, with the Dallas location also manufacturing various pool products. Later in the decade, the firm acquired Pioneer Pools Corp., a New Jersey-based package-pool manufacturer.

For its part, Blue Haven used many of the same tactics to achieve enormous growth. In 1962, the company completed a public offering of 55,000 shares of stock at $4 per share. The purpose was to raise capital for expansion. No doubt, part of those funds went to pay for a “Pool Super Mart,” which debuted in Southern California in 1963. One of the first large-scale showrooms seen in the industry, the Mart’s grand opening featured a full aquatics show, clowns and prize drawings.

In 1964, Blue Haven announced its intent to expand nationally, and over the next couple of years opened branches in Texas and across the Midwest. The firm also was heavily involved in manufacturing, and in 1967 began to offer a whopping 10-year warranty on equipment, called “the first of its kind in the industry.”

But the two industry juggernauts weren’t alone.

Newcomer Shasta Pools burst onto the scene in 1965, effortlessly surfing the construction wave that swept over Phoenix. In 1966, Shasta built 26 pools. The following year, that number increased to 248. In 1968, it stood at 535.

Four of the top five firms on the Pool & Spa News Top 50 Builders list in 2011 were doing a brisk business in the 1960s, a testament to these companies’ strategic and entrepreneurial skills. They include Blue Haven Pools & Spas, Anthony & Sylvan Pools, California Pools, and Paddock Pools and Spas. Shasta Industries was No. 6.

Growing pains

Those heady days of being in on the ground floor of a runaway new product also carried a price.

Almost from the moment the industry was born, there were unethical builders hovering like flies on a thoroughbred. And as early as 1963, the Better Business Bureau was instituting stings.

At the time, bait-and-switch advertising was rampant, and the BBB began secretly recording the pitches of pool salesmen in an effort to snag builders making false claims.

The problem was compounded by a mysterious sales slump that gripped California in the middle of the decade. While the industry nationwide saw record growth, builders in the largest pool state watched in horror as permit numbers dropped, culminating in a plunge of 42 percent in 1966.

That year, builders and manufacturers held a meeting called, rather hopefully, “Operation Optimism” aimed at solving the problem. They blamed the issue on a number of factors, most notably public distrust of the industry.

“It’s not uncommon to have a salesman tell a prospect, ‘Why don’t you get another bid, call me back and I’ll beat it,’” said Jack Berg, president of Blue Haven. “The customer gets entranced with the low-ball price, and when the salesman then tries to talk him into the price he should be getting, the customer becomes pretty disenchanted.”

During that time, many large firms declared bankruptcy, including Orinda Pools, which left more than 100 unfinished projects in its wake. Fortunately, the industry did recover nicely, and the rest is history.

“Our business isn’t like yo-yos or skateboards,” said NSPI President Phil Bulkeley in 1964. “Ours will stand the test of time.”

While he may have been wrong about the first two, he was on target for pools.