Supply and demand: American firms can already produce more chlo…

In Tennessee, where Memphis Pool expects to maintain 400 pools a week this summer, Mark Reed is keeping a close eye on the cost of pool chemicals.

“I’ve heard some rumors that chlorine prices will be increasing,” says Reed, the company’s president, who says pool chemical pricing has held steady so far. But he isn’t taking any chances. “We did place some larger than normal orders, hoping to beat the increase if it happens.”

Others say such increases are inevitable. “Chlorine prices go up 3 percent every six months,” says Bryan Chrissan, owner of Clear Valley Pool and Spa in Temecula, Calif., which currently maintains 45 pools and does bulk buys of chlorine to control costs. “It’s like gasoline. I need it.”

Regardless of your firm’s approach to purchasing chlorine products, though, it’s worth knowing that the pricing and sources of this essential pool chemical could be changing in the months ahead. Why? The U.S. Department of Commerce and the International Trade Commission have been investigating allegations of unfair trade practices by overseas manufacturers of chlorine compounds such as calcium hypochlorite and chlorinated isocyanurates. Final rulings are not expected until later this year, but if the U.S. does put tariffs on these products in the months ahead, it will most likely impact the price of chlorine, regardless of where it was produced.

Accusations of anticompetitive practices against foreign chlorine producers are nothing new. U.S. manufacturers have filed a number of such petitions in the past. But the current trade investigations center on three countries and imports of two chlorine compounds, calcium hypochlorite and chlorinated isocyanurates, that are essential to water treatment and disinfection in pools and spas.

The American companies’ concern is understandable since globally, the world market for elemental chlorine, which encompasses more than just water treatment chemicals, is approximately 57 million metric tons, says George Eisenhauer, director of chlor-alkali at IHS, a research firm based in Englewood, Colo. Chlorine also is involved in the manufacturing of polyvinyl chloride (PVC), which is used for plumbing pipe and vinyl pool liners; used by the food industry in the creation of high-fructose corn syrup; and by energy companies in the growing practice of hydraulic fracking for shale oil and natural gas. “The oil and gas industry has become the biggest consumer of the hydrochloride molecule,” says Eisenhauer.

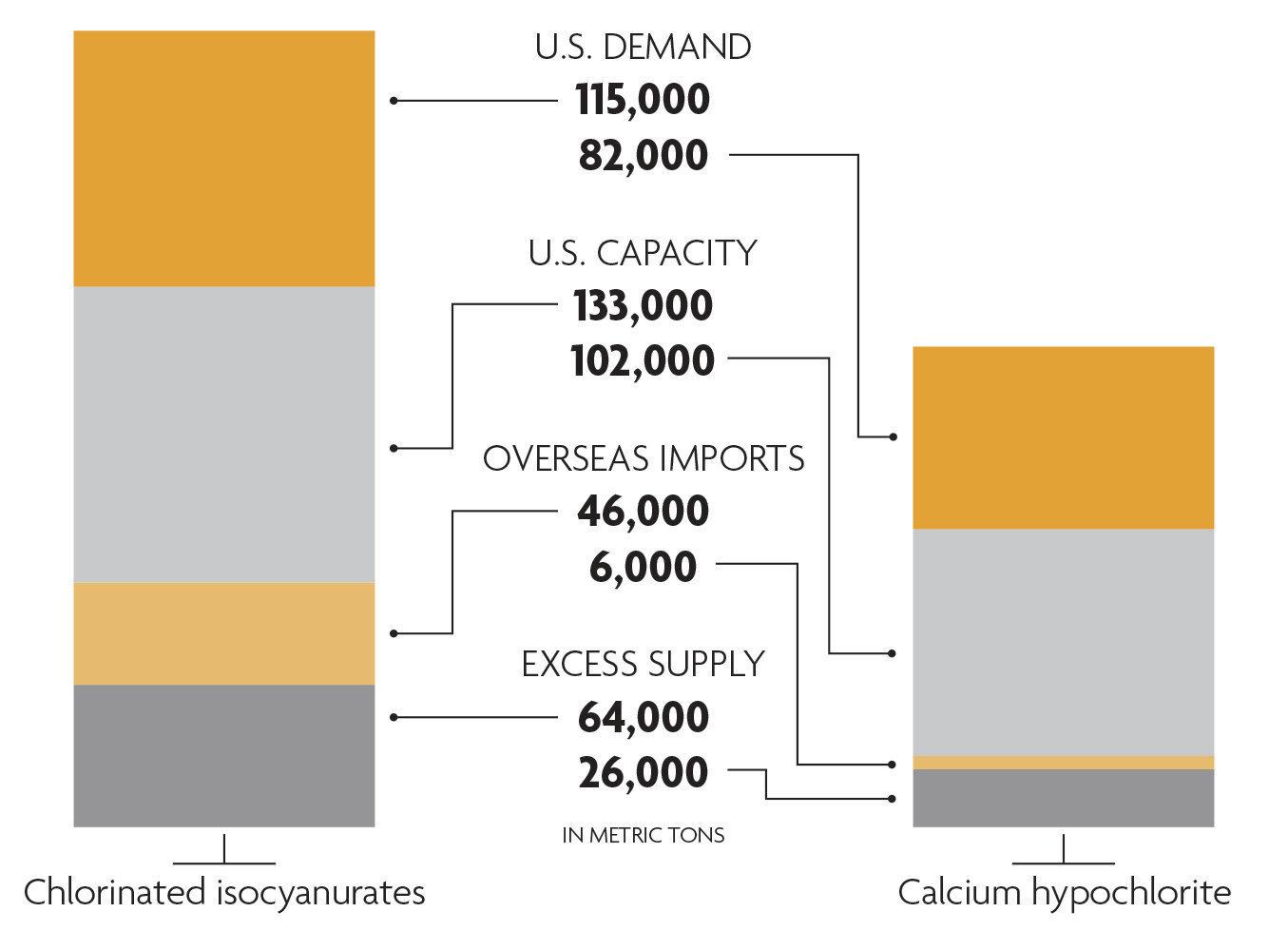

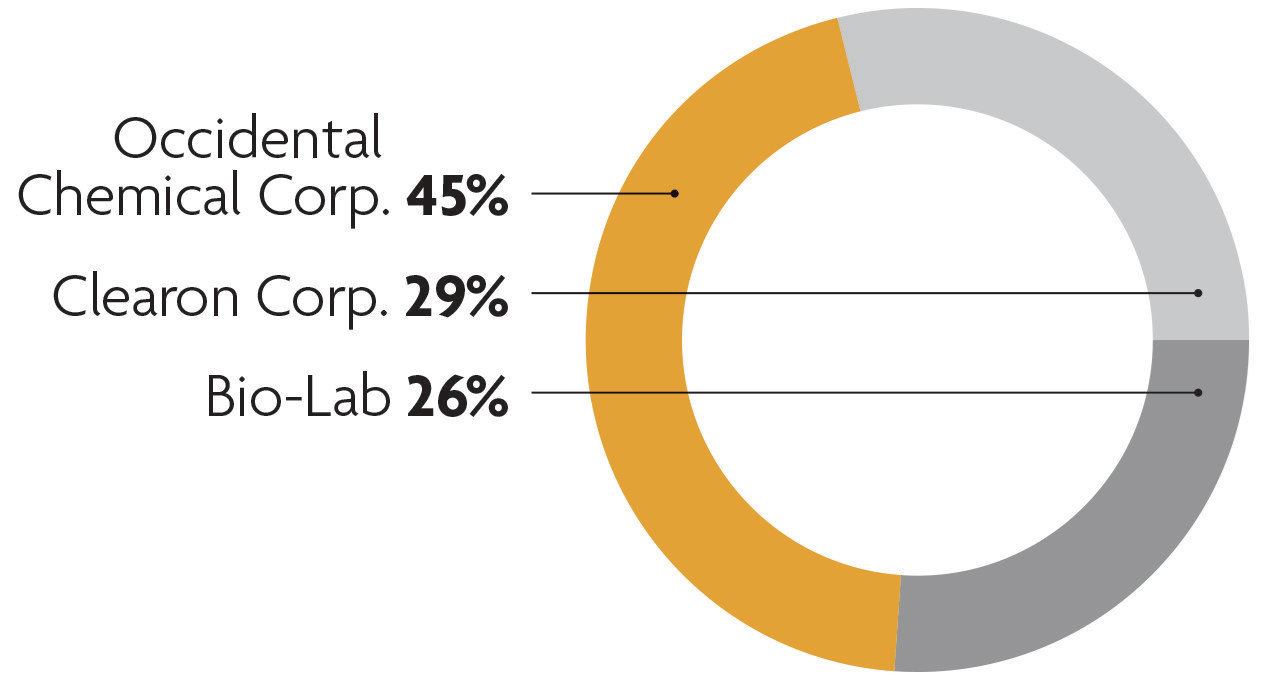

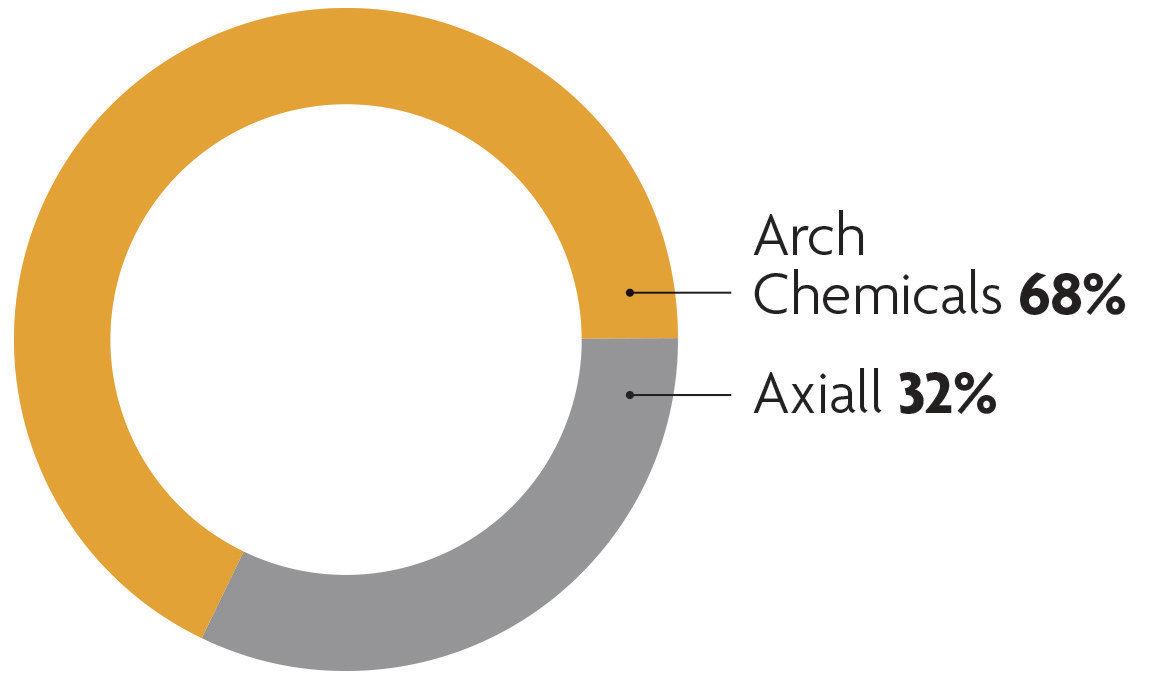

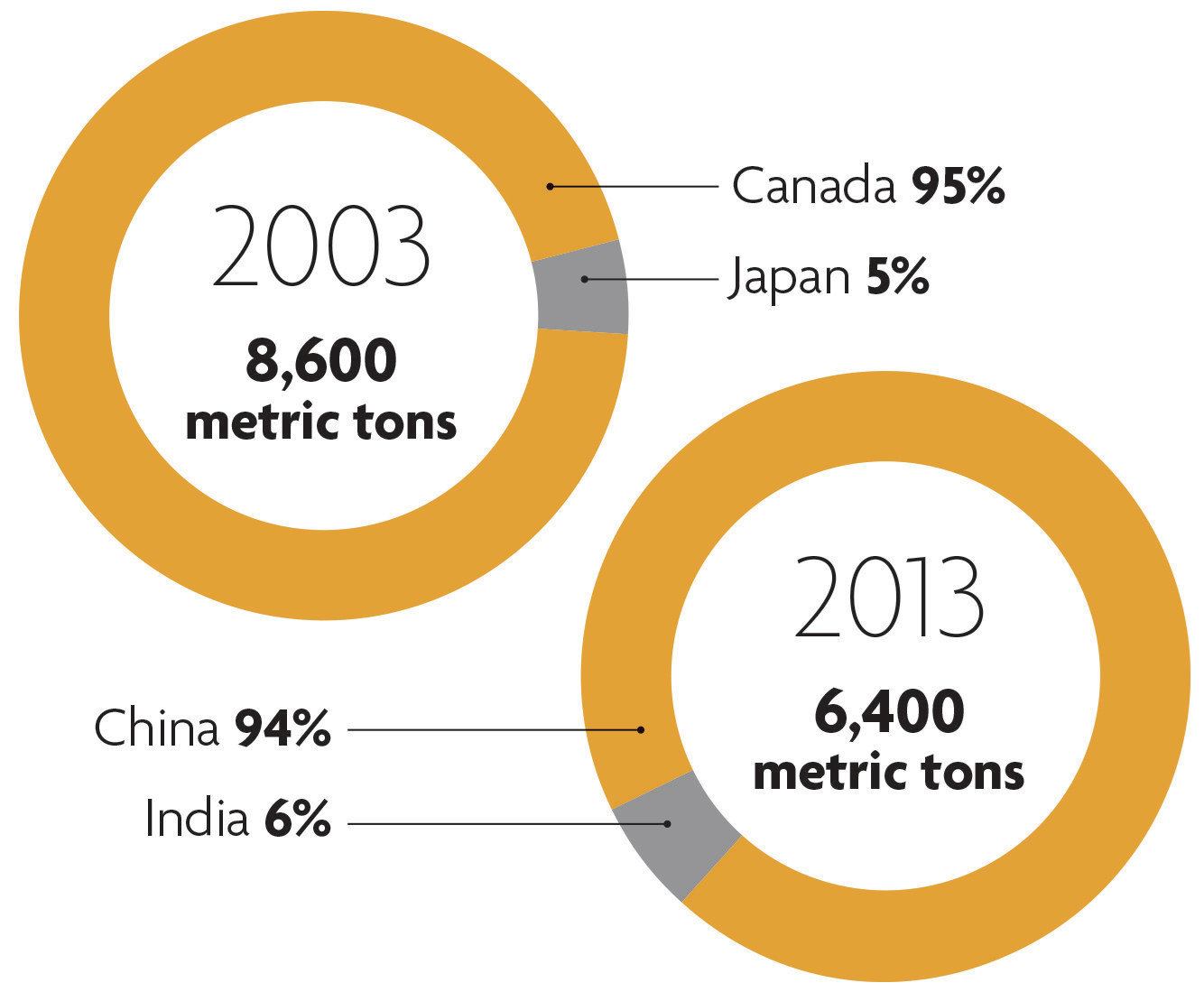

Water treatment also is big business; the wholesale market for pool chemicals during the industry’s peak in 2007 was $2 billion, according to Chemical and Engineering News. Domestically, just a handful of companies —Arch Chemicals, a Lonza company; Clearon Corp.; Occidental Chemical Corp.; and Axiall — control most of the production of cal hypo and chlorinated isos. It adds up to lots of chlorine compounds — more than the American market needs, actually. According to Eisenhauer, the U.S. has the capacity to manufacture more than enough chlorinated isos (133,000 metric tons) and cal hypo (102,000) than required. (See “Supply and demand” chart.)

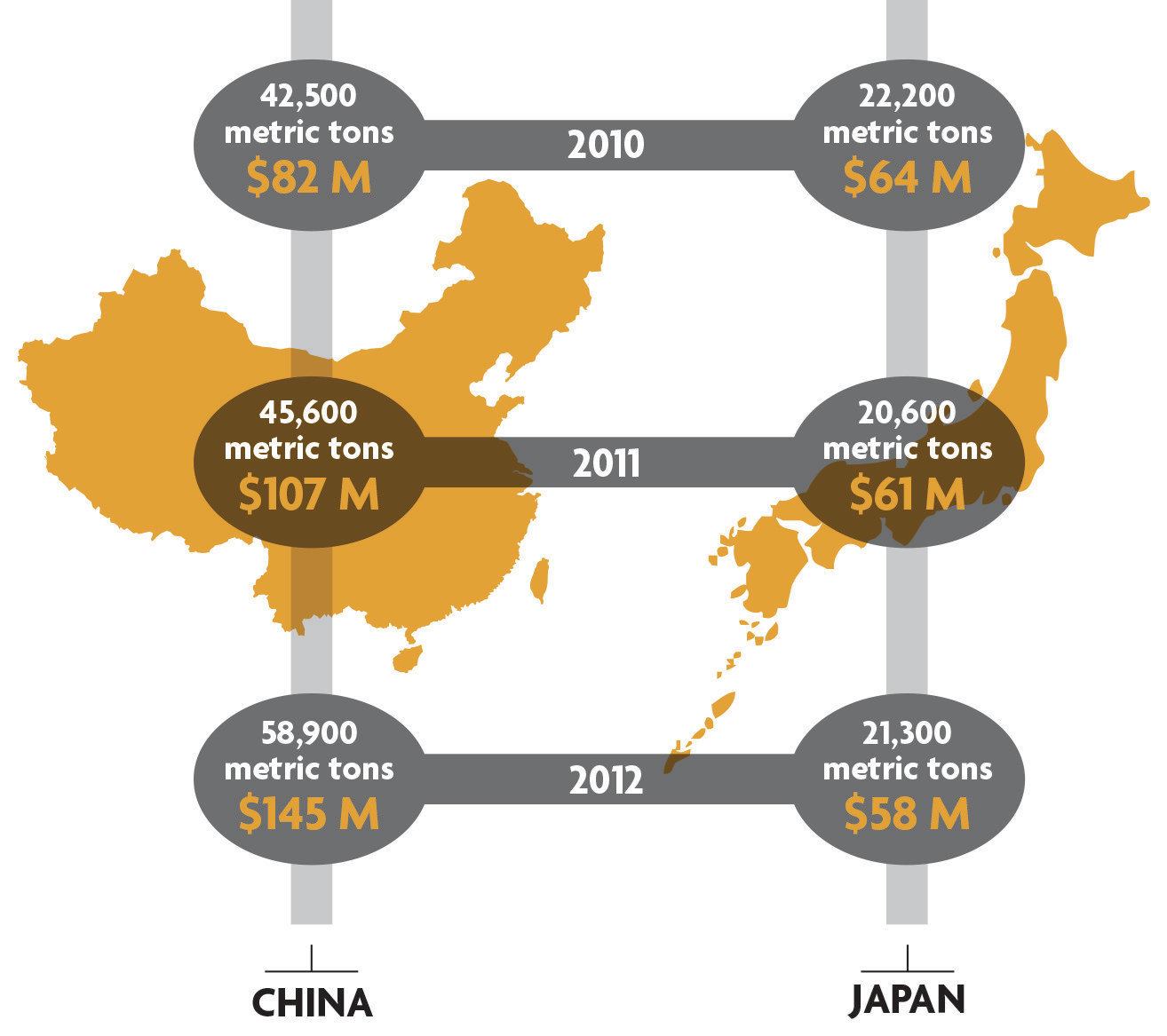

Yet Chinese and Japanese producers imported more than 80,000 metric tons of chlorinated isos into the U.S. market in 2012.

Last year, Occidental and Clearon cried foul, filing a petition with the ITC. Occidental declined to speak with Pool and Spa News for this story and Clearon did not respond to requests for comment, but in their petition, they argued that foreign firms were highly subsidized by their governments and, therefore, were able to sell their chlorine products at below market value. The Japanese report is still outstanding, but in February, the federal government agreed that Chinese firms did appear have an unfair advantage against American companies. In its preliminary report, it found that Chinese imports of chlorinated isos were receiving subsidies of nearly 2 percent to almost 19 percent, depending on the producer. A final decision, which involves the Commerce Department and the ITC, is expected sometime this summer.

The cal hypo situation is very similar. Arch Chemicals, the largest U.S. producer of cal hypo, also filed its own petition in 2013 with the International Trade Commission, arguing that Chinese imports were artificially depressing prices for cal hypo. (Arch was contacted for this story, but was unable to speak with Pool and Spa News until after our deadline.) In January, the ITC agreed that American companies were probably being harmed by subsidized Chinese imports of cal hypo, but it has not determined what the subsidy rates might be. It expects to release those details sometime this summer.

Why are foreign firms importing so much cal hypo and chlorinated isos into the States?

Eisenhauer says it’s a combination of market forces and chemistry. In Asia, chemical companies have plenty of chlorine to spare, thanks to high demand for and production of caustic soda. Used in soaps, organic and inorganic chemicals, and alumina, caustic soda is the highly desired byproduct of the chemical reaction that creates chlorine. And, because they are making so much caustic soda, they have lots of extra chlorine, which gets exported to the United States and sold at low prices. “The chlorine molecule basically has a negative value to them,” Eisenhauer explains.

The situation is a challenging one for American firms. In a written statement, the American Chemistry Council, a trade group for chemical companies, praised the decision by the U.S. government to look more closely at the chlorinated isos market: “The American Chemistry Council’s Chlorine Chemistry Division and its members support a fair and free market for chlorinated isocyanurate products. We are pleased that the U.S. Commerce Department is conducting a thorough investigation under U.S. countervailing subsidies laws.”

What happens if the U.S. decides definitively this year that Chinese and Japanese companies have an unfair advantage? The feds might decide to place what is known as a countervailing duty on these chlorine products, which softens the impact of those subsidies by effectively raising the prices of these imported products.

That, of course, will affect what pool firms will pay for these common water treatment chemicals. “If there is a tariff of X percent, then the price will go up X percent, or the equivalent of the tariff,” Eisenhauer explains. “But prices may also decline [before the tariff becomes effective], because countries will try to ship more product into the U.S. before the tariff makes the prices go up” and causes their foreign product to look less affordable to U.S. buyers.

Such global factors for price increases can get a little frustrating for pool firm owners watching their expenses. “It’s like with concrete, when they said prices were going up because of the Olympics” and the related building projects, Chrissan says. “Really, that’s where it’s all going? I think it’s just another reason for them to charge more for their products.”

Chlorine wars

What: Ongoing investigations into the level and impact of foreign imports of chlorine compounds on the U.S. market.

Who: Clearon Corp., South Charleston, W. Va.; Occidental Chemical Corp., Los Angeles; and Arch Chemicals (owned by Swiss firm Lonza) have all filed petitions alleging unfair competition with the U.S. Department of Commerce and the International Trade Commission.

Chemicals: Chlorinated isocyanurates (Occidental and Clearon) and calcium hypochlorite (Arch).

Why: These manufacturers say that Chinese and Japanese chemical companies are hurting American firms by illegally flooding the U.S. market with cheap chlorine compounds.

When: Occidental and Clearon filed theirs in August 2013; Arch filed its petition in December 2013.

Status: The International Trade Commission decided in January that evidence suggests that Chinese imports of calcium hypochlorite are hurting American manufacturers. It is investigating whether to place additional duties on the product; a ruling is expected sometime this summer. In February, the agency also decided that Chinese imports of chlorinated isocyanurates were being significantly subsidized by the Chinese government; it is still investigating whether Japanese imports were subsidized. Rulings in the chlorinated isocyanurates cases are expected this summer.

Why this matters: New tariffs on foreign chlorine imports could result in higher prices for all chlorine products in the United States, even if they are produced here.