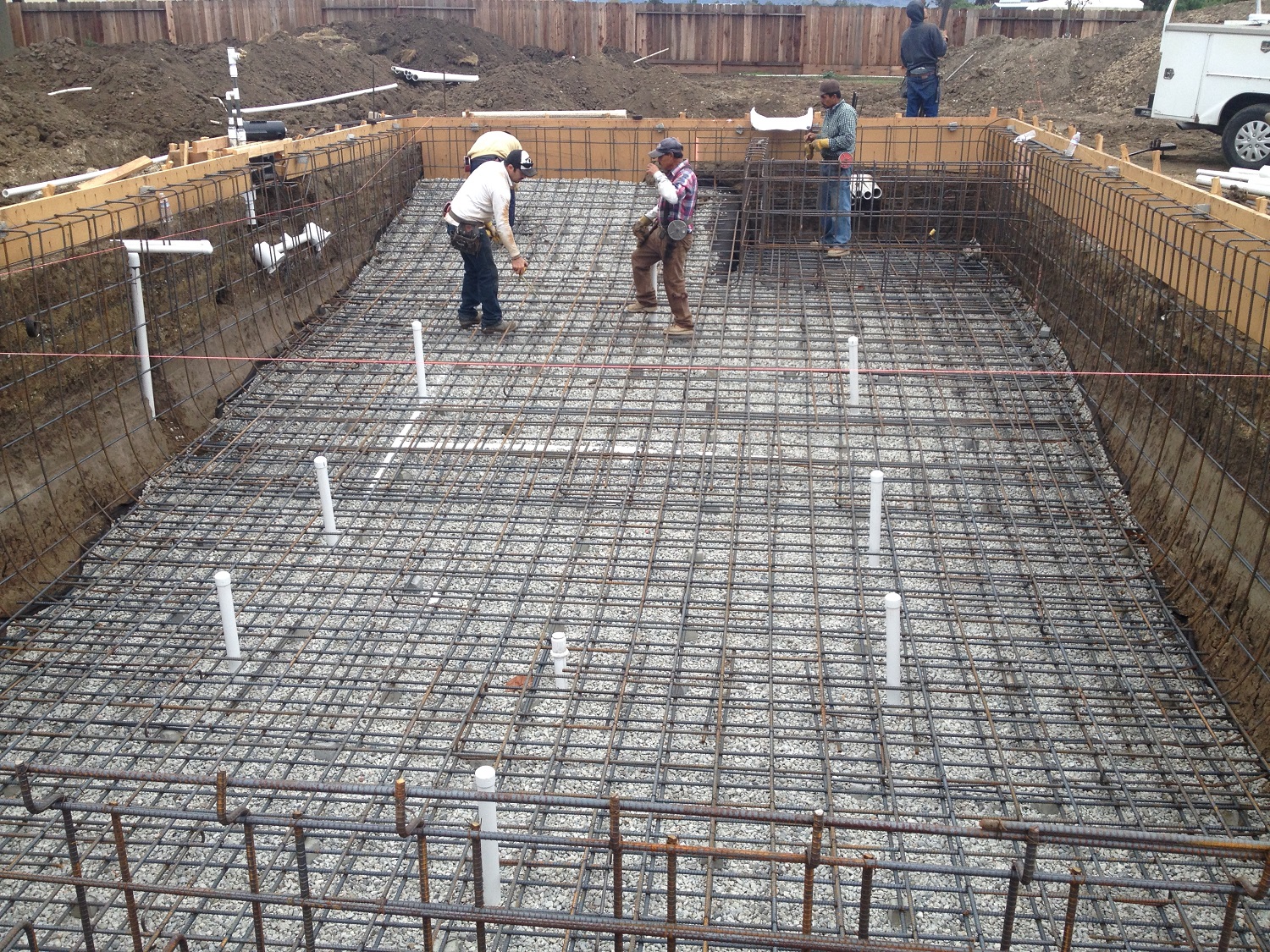

Courtesy Aquatic Technology Pool & Spa

While most municipalities only mandate them on commercial installations, non-contact splices are recommended by the American Concrete Institute for every pool and spa. They are more difficult to tie and some don't like how crowded they can make the grid seem. For some, the question of whether to require non-contact splices boils down to how much a builder trusts the shotcrete applicator to get the concrete around the bars.

These photos show shadowing, in which shotcrete fails to properly compact behind the rebar. Here the concrete is not monolithic in the space behind the steel.

Courtesy Watershape Consulting

These photos show shadowing, in which shotcrete fails to properly compact behind the rebar. Air voids in the space between bars contributed to the cracking of a pool shell.

The beauty of reinforced concrete is the marriage of the cementitious material with steel rebar. The concrete provides strength against compression, while steel can bend and move with tensile pressures.

In an ideal world, the rebar reinforcement would be non-stop and go all around the pool’s or spa’s perimeter. But, understandably, they don’t make bars that long, so steel ties must connect multiple pieces of rebar using lap splices. These overlaps from one bar to the next allow tensile force to transfer from bar to bar.

“If you’ve lapped the bars at least [the right length], then whatever force is in one bar can be transferred to the other bar,” says David Peterson, president of Watershape Consulting in San Diego. “So from a structural standpoint, they behave as though there’s just one bar.”

Here, professionals discuss the considerations that go into lap splices.

Proper transfer

The length of the lap is a crucial component in its success and is determined by several factors.

Generally speaking, the more tensile strength the rebar carries, the more must transfer, and so the larger the laps needed.

This depends not only on the size of the bar, but also the grade. “If you have a grade 40 steel, you have a tensile strength of 40,000 psi, versus a grade 60 which is 60,000 psi,” says Noah Smith, a senior associate with Neil O. Anderson and Associates, a Terracon Company, in its Concord, Calif. office.

“You want to transfer the full tensile strength from bar to bar, so the higher the tensile strength of the grade of the steel, the longer the lap splice you’re going to need to develop that load transfer.”

If epoxy-coated rebar is used, another 20 percent of length must be added to the laps, since the smoother surface of this product reduces the ability of the concrete to grab on (which is why this material rarely is recommended for pools).

“It’s like a tug of war,” Peterson says. “If you’re in a tug of war, and you’ve got weaker concrete or weaker guys pulling, you need more of them. If one team has uncoated bars, they can really grab onto it. If the other team has got epoxy-coated bars, their hands are slipping, so you need another 20 percent more people pulling on that bar.”

An old rule of thumb for lap length said to use 40 times the diameter of the rebar for grade 40 steel; 60 times for grade 60. Now, however, engineers recommend either following their specifications or consulting the equation in ACI 318, the American Concrete Institute’s standard for shotcrete placement.

Placed correctly

In addition to ensuring the proper length for adequate strength, contractors also must ensure that the splices do not interfere with concrete placement.

Because the configuration of a splice involves two bars next to each other in spots, this has the potential to create voids in concrete that is pneumatically applied. As the shotcrete contractor shoots, the material’s pathway to the vertical wall could be hampered by the steel if it’s not placed properly. This can create small voids behind the rebar, a phenomenon known as shadowing.

To avoid this problem, contractors should set the steel so it is as unobtrusive as possible to the flow of the concrete. The most common method is to stack the laps one on top of the other, so they create a plane that’s perpendicular to the wall or floor behind it. If the steel is formed on a wall, for instance, the laps should be stacked out, toward what will be the inside of the pool.

This way, when the shotcrete applicator aims the nozzle, he or she sees one bar in front of the other, and only has to shoot around one bar width. Note, however, that because the steel will take up more thickness within the shell, the concrete may need to be shot thicker to ensure proper embedment of the steel — in most cases that means 3 inches of concrete from rebar to soil, 2 inches of stack-lapped bars (using No. 4’s) and 3 inches of concrete to the water, for a total of 8 inches minimum.

Contact or not?

But some believe this is not enough to prevent shadowing.

For most installations, the American Concrete Institute 318 code requires contractors to create what are called non-contact splices. Using this method, the laps are separated by 2- to 4 inches, set on a plane that’s parallel to the wall or floor behind it. This way, when the contractor shoots, the concrete can flow behind the bars and hit the vertical surface behind, then wrap around the bars as the concrete builds.

Many contractors avoid non-contact splices if they can, because they’re more difficult to tie. They require extra steps and ties to keep the laps separate.

“When you separate them, you’re basically putting two extra ties in, because you’re putting four ties in instead of two,” says Paolo Benedetti, president of Aquatic Technology Pool & Spa in Morgan Hill, Calif. “You’re having to tie the end of each bar off to the perpendicular bar crossing under it or going over it, so that tip isn’t bouncing when they’re shooting or walking on it.”

Others object to the fact that they make the grid more crowded, with the laps being set 2- to 4 inches apart. This can cause more rebound as the concrete bounces off all the steel, they believe.

SEE MORE: Avoid these mistakes when reinforcing concrete

While most municipalities only require non-contact splices on commercial installations, some builders believe they should be used for all pools. Benedetti requires this of his steel contractor, citing the International Building Code.

And while many find non-contact splices more difficult to make, Benedetti believes they’re actually easier than the alternative in some cases. If a local jurisdiction requires non-contact splices, they may allow the contact method when the contractor provides test panels. Engineers also may require this on certain jobs if they prefer non-contact splices. To create the test panel, the contractor must shoot a specified area of shotcrete, say 4-by-4 feet, with reinforcement in place. Then the engineer or government official inspects it to see how well the rebar is encased. Neil Anderson, principal of Neil O. Anderson and Associates, a Terracon Company, might be more prone to require this for a dry shotcrete, or gunite, job.

For Benedetti, this presents more of a hassle than just tying the steel with non-contact splices.

“In the IBC, it says the use of contact lap splices shall only be permitted when you show through tested demonstration that you can shoot and not get shadowing,” Benedetti says. “Nobody wants to go through the expense of shooting test panels. Nobody wants to jump through those hoops to do contact splices, so it’s easier just to do non-contact lap splices.”

Contractors may find non-contact splices easier to install in the floor: On a horizontal surface, the laps will remain separate with gravity’s help. For the wall, the contractor must maintain the separation on a vertical plane, so it can prove challenging to keep the stacked bars upright.

Non-contact splices also may be most appropriate for projects where the steel surpasses a certain size. For No. 5 bars, Anderson always recommends this method. With the bars more than ½ inch in diameter each, butting the two together creates more than a 1-inch width, which can make the job susceptible to shadowing.

For others, the question of contact versus non-contact splices comes down to the trustworthiness of the shotcrete applicator. “The truth is a really good shotcrete crew could still succeed with contact lap splices,” Peterson says.

Either method is fine for cast-in-place or poured concrete, since it will be compacted through vibration rather than the velocity through the nozzle.

Other considerations

Regardless of the types of splices being used, installers should stagger or offset them so they aren’t lumped together in certain areas. This helps preserve the integrity of the concrete. Too much steel clustered together can interrupt the material’s integrity.

Many contractors also recommend that laps not be placed in the corners to avoid congestion of the steel.

“If it looks like bars are going to start ending in the corners, I tell the guys to just cut them back a few feet, then wrap a bar all the way through the corner, and use a whole bar,” Benedetti says. “You end up with a few scrap pieces of steel here and there, but it’s no big deal.”