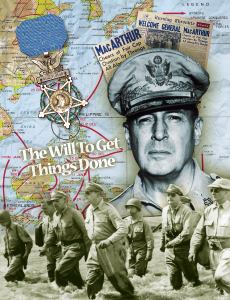

Douglas MacArthur

For John Norwood, the World War II hero and architect of modern Japan taught lessons in standing your ground.

Douglas MacArthur had no problem seeing his place in history. “I believe it was destiny,” he once told a New York Times reporter who had asked about his accomplishments.

But whether fate played a role, the five-star general has inspired John Norwood with lifelong lessons that he applies to his work to this day.

“There’s no doubt that he seemed to have an ego,” says the president of SPEC , the California pool industry’s advocacy group. “But when you look at his overall history from World War I forward, I guess he should have had some ego.”

MacArthur possessed a rare combination of steadfastness, adaptability and innovation. He did whatever it took to achieve a goal. Sometimes this made people see him as too extreme, other times too soft.

“He was a military genius,” Norwood says. “But besides that, he was a real student of democracy, humanities, education — the spirit of the individual.”

MacArthur’s oversight of Japan’s post-World War II reconstruction presents one of the starkest examples of these qualities. Having cemented his place in history as the second-most-decorated American officer in World War I and the mastermind behind World War II’s Pacific theater, MacArthur became the supreme commander of the Allied powers in Japan in 1945. He had helped bring down that nation; now his job was to build it up.

His vision was to transform the predominantly agrarian monarchy into an economically thriving, capitalist democracy. So deep was his influence that Time Asia included MacArthur in its series “60 Years of Asian Heroes.”

“He was a strong advocate of the individual, equality and economic freedom, and the ability to put more food in your stomach and a roof over your head,” Norwood says. “He built Japan into a strong democracy, to be kind of an outpost of freedom in the Far East.”

But he ruffled more than a few feathers along the way.

One of MacArthur’s first actions was to help alleviate the potentially catastrophic food shortage there, acting against the Allied powers’ wishes to stay out of Japan’s economic rehabilitation. He configured the Army kitchens to feed the Japanese with local food, believing that thousands otherwise would have perished.

Those under MacArthur’s command were forbidden to eat anything besides the 3.5 million tons of Army food that were brought over from other Pacific locations, at an expense he would later have to justify to the U.S. Congress.

This seemed to establish trust in MacArthur among the Japanese authorities.

But perhaps MacArthur’s most controversial action was his decision not to subject Emperor Hirohito to prosecution. The Allied nations wanted to see Hirohito tried as a war criminal, but MacArthur believed that although the monarchy had to be divested of power, prosecuting the emperor would cause rebellion.

Many thought the emperor and key members of his family should have paid for the country’s crimes, and that MacArthur’s choice was based in corruption. But to Norwood, the tactic showed an awareness of the big picture.

“One of the things he really understood was the history of these countries and civilizations,” Norwood says. “If he was going to rebuild this country [that] was already destroyed and torn apart, he probably felt he had to do it in a way that was respectful of its culture.”

MacArthur’s strategy seemed to work. In just five years he greatly reduced the royal family’s influence, created a democracy and a capitalist economy, and gave women the right to vote. He also vastly improved health care: Some say average life expectancy increased up to 14 years during this time.

MacArthur has said that of all his achievements, he’d like to be remembered most for what he accomplished in Japan. Unfortunately, it’s his next assignment that comes to mind first for many, and it ultimately spelled his downfall.

The setting was Korea, shortly after his stint in Japan had ended. MacArthur brought victory to the conflict when some didn’t think it could be won, combining air strikes with an amphibious landing to push the well-manned, highly trained North Korean units back across the border.

But then came the butting of heads with President Harry Truman. When the Chinese attacked U.N. forces, MacArthur wanted to strike back, yet Truman opposed the idea, fearing the Soviet Union would become involved. MacArthur made his disagreement with Truman very public. More seriously, MacArthur issued an ultimatum to the Chinese, laying waste to Truman’s diplomatic efforts. As a result, he was dismissed.

What some would call insubordination, others believe was just the flip side of the man’s greatness.

In any case, his many supporters don’t let a sour ending detract from a lifetime of accomplishment and progress.