The past few years have been tough for the pool industry, but three notable companies have managed to expand not only in spite of the Great Recession but, in some cases, partly because of it.

Northern California-based builder Premier Pools began a licensing program to spread its brand around the country. Georgia service firm America’s Swimming Pool Co. (ASP) debuted a franchise operation. And national retail chain Leslie’s Poolmart accelerated its growth significantly.

These companies have managed to thrive in a terrible economy, and they did it using business models that usually don’t succeed in the pool and spa industry. Though it’s true that other firms have recently grown, few have done so on a national or even multi-regional level.

Here, the company principals and industry observers discuss the reasons behind Premier, ASP and Leslie’s success.

Breaking out

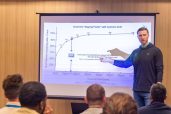

Overseeing a corporate-owned chain or a network of franchisees not only requires industry knowledge but also the ability to duplicate a business model by developing procedures that apply to different markets. That process can fall beyond the training of some pool professionals.

“You start in the hole in this business,” says Paul Porter, CEO of Premier Pools, headquartered in Rancho Cordova, Calif. “You start digging and steeling and plumbing, but nobody ever teaches people how to run a business.”

This is particularly challenging for building firms, which must deal with regional issues such as soil conditions, says Jeff Fausett, president of Aquatech Corp. in Costa Mesa, Calif. “People who have tried this regionalization theme have failed because they don’t have enough management experience,” he says. “They’ve always been good at doing pools in their own backyard, but when you go to another state, you have to manage problems from a long way away.”

And beyond skill level, there’s the culture of family-run businesses that make up the industry’s backbone. Many companies were started by professionals interested in owning an operation that would involve multiple family members. There isn’t always motivation to grow. Plus, such operations don’t often generate the kind of capital needed to fuel large expansion.

“These aren’t businesses that make $40 million per year at each location,” Fausett says. “They’re getting by — making anywhere from $500,000 to $2 million in each location. That doesn’t give you a lot of overhead for infrastructure.”

Running a chain, franchise or other such model also requires a different mindset. The CEO must let go of managing the original locations to focus full-time on the entire corporate structure.

“The hardest thing you would have to do to franchise your business is let go of operating a location that’s your bread and butter,” says Stewart Vernon, founder of ASP, based in Macon, Ga. “You’ve got to be able to totally relinquish yourself from that and focus solely on the franchise system. That’s a very difficult thing to do.”

Because of the relative newness of Premier’s and ASP’s efforts — two and six years, respectively — it will be awhile before one can say definitively that they’ve been successful in the long term. But results so far indicate that they’ve found a formula that works.

Filling a need

Though ASP’s existence didn’t rely on the recession, Vernon believes that his company’s meteoric growth was helped by the economy.

After graduating from college and owning his own service company for about five years, Vernon began his franchising operation in 2006. He wanted to put his business and communications degree to work by developing set procedures for each franchisee to follow, then recruiting people with a mind for business, mostly from outside the industry, so they could be trained without preconceptions. Vernon gave up his original location, selling it to his first employee so he could focus on the franchising plan.

Vernon didn’t expect his company to grow so quickly — the current count is 100 territories in 11 states. Because of its success, the firm was listed last year on Entrepreneur’s “Top 100 Fastest Growing Franchises.” Vernon attributes this largely to his business background, along with that of his core team.

But the economy definitely had a role to play. “We have seen our most significant sales increases and expansion from 2009 through 2012,” Vernon says.

The downturn and its resulting layoffs produced an abundance of intelligent, driven individuals capable of protecting the ASP brand and ready to start a new chapter. “I think the word entrepreneur has really taken on a new meaning since about 2010,” Vernon says. “Franchising, especially in our industry, is a way for someone to enter a very low-cost, low-overhead business venture and become their own boss, and that’s what we offer them,” he adds.

Testing a new model

Though the recession hit the building sector hardest, it also proved to be a significant driver for Premier’s model.

Porter began implementing his growth strategy in 2010, when volume in some markets had dropped as much as 90 percent. At the time, he and partner Keith Harbeck owned 10 offices in California and Arizona.

They decided to try turning Premier into a national name by partnering with existing builders who would purchase rights to the brand and access to support. Harbeck assumed ownership of Premier’s flagship operation in Rancho Cordova, Calif., and Porter took over the corporation. The other nine existing Premier offices were sold and licensed, primarily to employees, to help fund the expansion and allow Porter to run the corporation.

“We gave up an asset that was worth millions of dollars to go on this model,” Porter says. “It was a big risk, but it was really a matter of survival.”

The timing was no coincidence. Porter had approached builders before the recession to discuss possible parnerships. “From 2000 to 2006, there was no receptive ear,” he says. “Everybody had more work than they could handle. Everybody was making a lot of money. So for me to say the industry needs to consolidate, create economies of scale, create more [unified] marketing… They were saying, ‘Why?’”

But after the recession hit, Porter’s idea made more sense to builders. “If we’re ever going to grow, if we’re ever going to have a national brand, then this is the time to do it,” Porter says.

Currently, Premier has 52 offices in 15 states and India.

Long-standing success

Leslie’s story has been different. Founded in 1963, the company has been operating as a national chain for decades.

Founders Philip Leslie and Raymond Cesmat began their multi-branch model shortly after opening, spreading first throughout the Los Angeles area. In 1988, the corporation began its foray into investor backing, when the venture capital firm Hancock Park Associates purchased it. A few years later, part of the company’s stock was put up as an initial public offering, enabling Leslie’s to see substantial growth throughout the 90s. But in 1997, the company went entirely private again, when Hancock Park partnered with private-equity group Leonard Green & Partners.

In 2010 Leslie’s began another aggressive growth jag, again fueled in part by funds from private equity. London-based firm CVC Capital Partners purchased 49 percent of the company’s stock, while Leonard Green & Partners retained a stake. That growth has included the opening of new branches, as well as some high-profile acquisitions. In 2010, the firm acquired Solutions by Self Chem, a retailer based in the Austin area. In 2011, the retail giant bought Phoenix-based Jasper’s Clear Pool Wholesale Supply Co., a supplier and service company geared to the commercial market.

Then, earlier this year, Leslie’s purchased the retail arm of Shasta Industries, one of the nation’s largest pool builders and a Pool & Spa News Top Builder.

In 2010 Leslie’s added 30 locations; last year it saw 50. And in January, Leslie’s CEO Larry Hayward said he expected another 60 openings and acquisitions this year. (Leslie’s staff did not return calls for this story.)

At the start of this year, Leslie’s had 750 stores in 35 states. The company has revenue of approximately $522 million, according to CVC Capital Partners.