From the earliest times, soaking in hot water has been a central part of human culture. Bathers around the world — from Egyptians, Babylonians, Romans, Greeks and Turks, to Hawaiians, American Indians and the Japanese — have eased their pains and enjoyed the social and spiritual experience of a shared hot-water soak.

In the United States, early inhabitants did their hot-water bathing in the continent’s numerous natural hot springs. European pioneers came to appreciate these geothermal waters as well, attaching claims of curative and restorative powers and making periodic treks to these hot springs a must throughout the centuries. Thermal springs occur in at least 21 U.S. states, but hot spots of early renown included New York’s Saratoga, California’s Calistoga and Georgia’s Warm Springs.

The Japanese have long had a tradition of keeping an ofuro — a free-standing, indoor tub typically made of teak — on hand for hot-water enjoyment, but it wasn’t until the 1960s that Americans began to catch on to the pleasures of hot-water soaking. Northern California’s counter-culture movement, as part of its search for new ways to experience the senses, began converting old wine vats — then plentiful in Sonoma County’s wine country — into watertight vessels stoked by wood-burning water heaters.

As the supply of winery leftovers grew scarce and demand steadily rose, consumers turned to cooperages (barrel makers) to build bigger and better tubs. These early hot-tub makers used California’s native redwood for beauty and endurance, or such exotic woods as teak, mahogany and Australian jarrah. More than just buckets of water, the tubs featured heaters, plumbing and jets to provide hot-water therapy on demand.

Consumer interest in hot tubs quickly expanded beyond Northern California. The industry’s early innovators, such as T.E. Brown, California Cooperage (since acquired by Coleman Spas), Gordon & Grant and Franciscan Hot Tubs soon began to offer the products nationally. The trend peaked just as spas stepped into the limelight in the mid-1970s, although wooden hot tubs remain a viable and much-loved product on the market today.

Heating Up the Spa Market

While wooden hot tubs flourished in the California sunshine, entrepreneurs began looking for alternate means to bring hot-water therapy to the home.

As early as the 1950s, pool builders had begun adding a separate, hot-water area to their pools. Termed “therapy pools,” they came complete with the predecessor to today’s jets, high-velocity return fittings.

As modern materials offered inventors the opportunity to develop a stand-alone unit that could be mass-produced and offer forceful jet action, the spa was born.

First and foremost among these innovators, Joseph Jacuzzi invented the portable whirlpool pump in 1954. One of seven brothers specializing in hydraulics, Jacuzzi developed a pump that could be coupled with air-injection jets to create the massaging air- water mixture that characterizes the jetted tub and spa experience.

Joe’s great-nephew, Roy Jacuzzi, continued the family tradition, patenting the first whirlpool tub in 1963 and introducing this “Roman Bath” to the public in 1968.

Like the computer chip that launched the home computer revolution, Roy Jacuzzi’s whirlpool patent set the ball in motion that led, by the end of the decade, to a new appliance for the home: the spa. Innovators experimented with shell and surfacing materials, plumbing, jets and spa packs to bring uniformity and affordability to the backyard therapy pool.

The first spas — gelcoat fiberglass tubs with equipment installed on site by a pool builder — debuted in 1970. In addition to Jacuzzi, pioneers whose work led to this included Joseph Everston, Len Gordon, Charles Barbara, James Kuehnle, Bill Baker, Bud Frank, Jack Stangle, John Silver, Dave Cavenah, Frank Howard and Bob Noble.

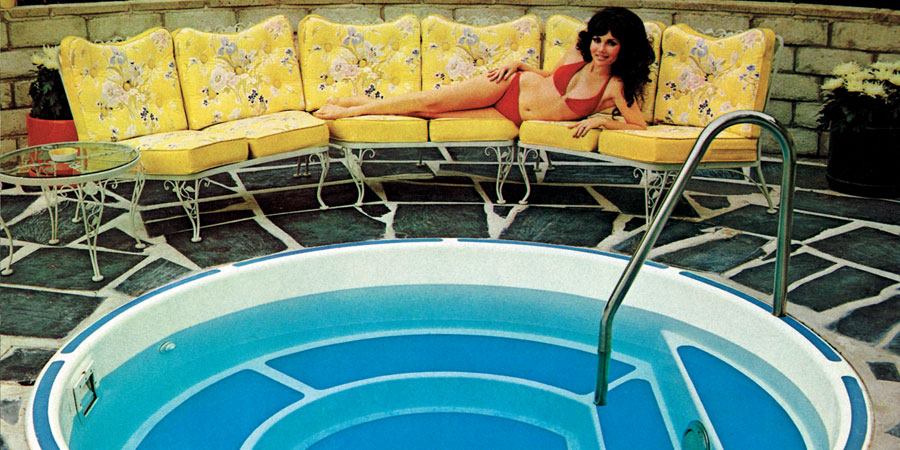

The gelcoat fiberglass surface offered a lightweight, durable material that could be mass-produced in molds, allowing for uniformity in the product’s hydraulics. As word spread, demand skyrocketed for these bubbling beauties.

While the fiberglass surface provided a viable alternative to gunite, it caused headaches for the industry as well. Spa owners complained about “The Black Plague” — stubborn black stains of unclear origin that appeared on the tubs. In addition, sun, chemicals and humidity apparently caused the fiberglass to blister and fade over time.

Hoping to staunch customer concerns, industry professionals looked for a better surface material — and discovered the beauty and versatility of acrylic. In 1972, Baja Products, led by co-founder Bernie Burba, working with Swedcast Acrylics introduced a fiberglass-reinforced, vacuum-formed acrylic spa shell. This soon became the industry standard, although some manufacturers successfully introduced other, proprietary materials.

Over the years, sheet acrylic makers Aristech Acrylics (formerly Swedcast) and ICI Acrylics have honed the surface’s form, function and fashion — creating new colors and textures.

Soon, manufacturers sought out ways to make the spas truly portable.

Moving On Up

Prior to the mid-’70s, most spa owners had the inground variety, with prefabricated shells and traditional pool equipment pads and plumbing. The emergence of the portable spa — an aboveground unit with plumbing and equipment concealed by redwood or cedar skirting — made the product affordable and available to a wider audience.

Most credit brothers Jon and Jeff Watkins with building the first self-contained and insulated portable spa while tinkering in their garage. Watkins Mfg. Corp.’s Hot Spring Spa debuted in 1977. By the end of the decade, companies such as Dimension One Spas, Sundance Spas, L.A. Spas, Coleman Spas and others had brought portable products to the market as well.

As part of the process, manufacturers reevaluated the spa’s equipment, which had been fashioned out of pool products not always suited to hot-water applications. In 1977, Brett Aqualine introduced the first spa pack, an all-in-one component system that united the pump, heater, blower, controls and plumbing. Later, the company would create a convertible pack that allowed continuous use of the heater.

Industry innovators found ways to use technology to enhance the spa’s appeal by adding spaside controls, so bathers could adjust the unit without leaving their seats. Many credit Len Gordon with dreaming up the first air-switch controls for spas, although other firms, notably Pres:Air:Trol, arrived on the scene at about the same time. Electronic switches and solid-state controls began showing up on spas in the 1980s, with Balboa Instruments among the innovators.

Topping off the new portable units, the first rigid vinyl cover was mass produced in 1980 by Sunstar Enterprises, working from a design by Watkins. Softub Inc. provided another ’80s innovation: the soft-sided spa, for true spa portability.

During the 1990s, manufacturers continued to hone portable spas, incorporating more high-tech and aesthetic features. Innovations include more spa sheeting and skirting material choices; jet adaptations for ever-increasing customization of the water massage experience; 100-percent solid-state spaside and remote controls; and time-saving options such as cover lifts and bromine generators.